Gospel for a New Century

Essay by Ruby Justice Thélot

“Capital has drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervor,

of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism,

in the icy water of egotistical calculation.”

- Marx & Engels, The Communist Manifesto (1848)1

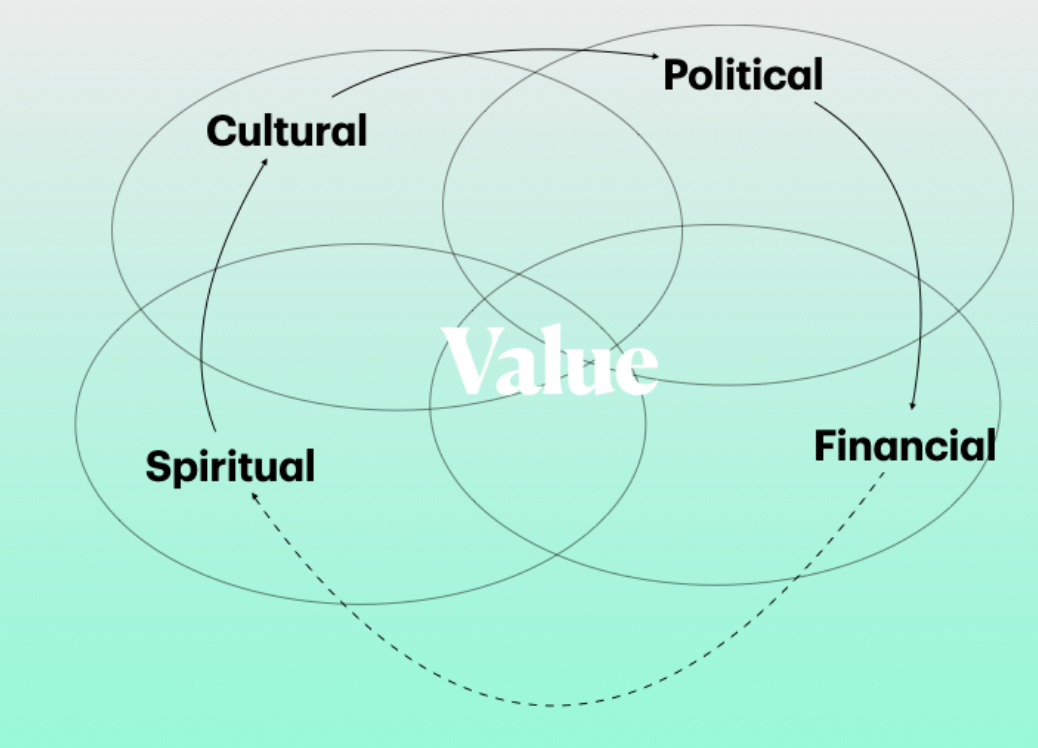

Last January, I gave a talk discussing the economics of digital art at Concordia University. I went over a history of markets in art, how certain platforms utilize user data to provide insights in buying, and, subsequently, I discussed the arrival of novel platforms and technologies that allowed for the sale of digital artworks. In the presentation, I map how art’s function changes over time.

Evolving from...

– “Spiritual”, referring to cave paintings and prehistoric art, similar to what David Rudnick calls “Art as an entryway to other worlds”

– To “Cultural” as a representation (read projection) of a cultural ideal similar to the return to classical Greco-Roman art during the Italian Renaissance

– To “Socio-political”, as a means to disseminate an idea, as seen with Constructivism’s view of art as propaganda, in the context of Soviet Socialism, and, in the West, how Abstract Expressionism was utilized by the CIA to disseminate occidental ideals such as the Free Market and Free Thought (read cultural colonialism)

– To the final stage being “Financial” or art as a store of value, as a financial instrument for speculation or trading or hedging

I believe the overlap of these areas as represented by the middle of the diagram can help explicate our current cultural moment, where some worship the ritual of transaction in order to further a crypto-optimist ideology.

Beyond Technomysticism

The systems of finance have always been deeply complex, but our modern financial system has increased exponentially in complexity over the past years, as elaborate financial instruments are created every year. This crisis of understanding became more palpable in the wake of the 2008 Crash, when subprime mortgages were repackaged into intricate securities that concealed the risk of the assets they contained.

It was around that time that a mysterious figure named Satoshi Nakamoto published their famous whitepaper “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System”, a concise explanation of how we could build a purely peer-to-peer version of digital money, that required no central banking authority, no trust—rather, it relied on an tamper-proof system called a “blockchain,” where transactions were recorded immutably. This, of course, requires faith in the technology.

In spite of the abundance of explanation videos and the brevity of the white paper, Bitcoin and cryptocurrency are still shrouded in an aura of mysticism. This may be due to the mysterious unknown figure of the creator, the foundational text, or even the forks in the protocol reminiscent of the schisms in the Christian Church—everywhere you look in crypto-communities there are symptoms of a certain Techno-mysticism. The complexity of these new technologies render them arcane to the uninitiated.

Cryptocurrency is revolutionary. For those who believe, it represents a paradigm shift—a new financial system, a new way of life, a new world.

After the US moved away from the gold standard in 1971, our currency (the US Dollar) became tied to faith (in latin, literally fiat)— faith in the capacity of central banks to curb inflation, faith in their ability to manage interest rates. Faith in the intellect and diligence of government officials. Faith in the US’s ability to maintain its military hegemony around the world and control countries where oil is produced. Essentially, faith in the US government and its military. So why not believe in something else?

How do you introduce and popularize a revolutionary idea—an idea so transgressive that most ridicule it? By looking at the history of religion, early Christianity more specifically, we can gather a historical narrative that informs us about the uphill battle proponents of cryptocurrency are facing. The need to find disciples, the need to proselytize, the need to perform miracles, the need to make people believe.

Crypto, for the faithful, represents a new system of thought and a complete rupture from an antiquated centralized system of governance—a radical ideology. History teaches us that at a certain point in its political rise, every new ideological system needs to create meaning not only in the realms of economy or society, but also in culture, as cultural prominence is an essential marker of hegemony (see: Cultural Colonialism). Enter NFTs, non-fungible tokens, the technology on which a lot of early crypto art is built.

Christ and Capital

Though some scholars hypothesize that the small amount of Christian art before 200 CE was amenable to a principled aversion to iconography inherited from Judaism, a better hypothesis is that early Christians, mostly poor at the time, simply lacked the land and capital to create their art, which required both. Hence, the loci of artistic production were catacombs and crypts, and the earliest creations were typically sculpted in sarcophagi.2

The Brescia Casket, 4th century CE. Image from WikiCommons

In line with Walter Benjamin’s understanding of the pre-mechanical-reproduction work of art3 as tethered to “ritual,” early Christian art was elegiac, meaning related to the rituals of funerals. However, it must be noted that as soon as the art left the crypt, the locus of tradition, of the ritual, it gained “entirely new functions,” as it also became, for the new religious communities, a political tool:a tool of propaganda.

Once Christianity was “legalized” in 313 CE, and prominent wealthy figures like the Emperor Constantine converted, Christianity began to accrue capital and land. Christians began to experiment with their own distinctive forms of art. Exquisite gilded codexes started being produced. The first large churches were built. These creations, though linked to certain religious rituals, also served as tools of dissemination of the Word (literally for the Codexes, and figuratively for the churches.) Each ekklesia was a node for a community to congregate. The newly affluent church deployed its capital in order to materialize and engender its own vision of the world.

Similarly, in the past years, as the number of token hodlers grew, and as the market capitalization of tokens such as Bitcoin and Ethereum rose, large hodlers in the community, also known as “whales”, emboldened by their newfound wealth, created and commissioned their own cultural artifacts. Metakovan, the collector who purchased work by Beeple for $69M at auction, addressed this directly in his post-purchase Clubhouse talk, where he clearly states that his goal is to “deploy capital” in a way that not only favors but engenders his worldview. He sought to utilize his capital as a productive force to adduce new cultural spaces where cryptocurrencies can reign.

The New Evangelists

One cannot preach to an empty church.

One of the main metrics crypto-enthusiasts track is adoption. Both because adoption tends to drive the price of the token they hold upwards (self-interest) and because adoption leads to the realization of the decentralized financial system they cherish (common good). A lot of capital is being deployed right now in the realm of NFTs as they represent to many Crypto-Optimists the next frontier of adoption. When art, especially non-rival and potentially viral content, exists on the blockchain, it showcases a very tangible use case for the technology. Furthermore, it materializes the ideology in a culture with its very own aesthetic codes, rules and idiosyncrasies.

Thusly, the success of NFTs as a tool for culture is crucial to the crypto project. When whales buy a Beeple for millions, and generate reporting from all media outlets, they are furthering the crypto project and the ideology as a whole. Think of it as building a big church in the middle of an important city to attract more newcomers, think of it as marketing to drive adoption.

Art found in the Catacombs of Priscilla, Rome, Italy. Late 3rd century / Early 4th century. Representation of the story of the “Three Hebrews in a Furnace”, a symbolic tale of tribulation and redemption through faith, as described in the Book of Daniel in the Ancient Testament. Image from WikiCommons.

Another large driver of conversions in early Christianity were miracles. Many occurences of miracles were caused by relics, i.e. physical remains of a saint. Interestingly enough, not only did these relics and their miracles drive new adopters, but they also benefited the communities who held them. In regards to relics, in “The Social Life of Things” (1986) Patrick Geary writes: "to the communities fortunate enough to have a saint's remains in its church, the benefits in terms of revenue and status were enormous, and competition to acquire relics and to promote the local saint's virtues over those of neighboring communities was keen".4 It was even common for local clergymen to actively promote their own patron saints and their realized miracles in an effort to attract more pilgrims. You can see the striking parallel with NFTs and the current platforms fighting for market share.

Representation of a miracle, “The Healing of the Bleeding Woman” from the Catacombs of Marcellinus and Peter. 4th century CE. Image from WikiCommons.

What then is the miracle of the crypto-art-sphere which attracts more pilgrims?

The sale.

This became apparent to me listening to Dylan Field, CEO of Figma, speaking about his former CryptoPunk (#7804), on Clubhouse. Field mentioned how in spite of loving it, he needed to sell it. He said, “It would never be considered as the Mona Lisa of Digital Art until a sale happened.” He sold the Punk for 7.5 million dollars. The transaction is what drives the media attention, not the valuation. The work of art shackled to the token cannot seem to survive on aesthetic quality alone. The valuation and the appreciation are latent, only through the transaction are they realized. In that sense, a “miraculous” NFT attracts people to the platform that showcased it. As digital artists, how can we resist? We observe the deeds and ask, by minting, that they be repeated in our days, to paraphrase Habakkuk. The transaction is what drives adoption. The sale makes people believe. The sale is the miracle.

Which begs the question: is the work of art in the age of digital reproduction still subservient to its parasitic relationship to ritual, the ritual of the sale?

Ruby Justice Thélot is a writer, curator, and artist based in Montreal, Canada. He is the founder of Sometimes Gallery, an online space for digital art. His work focuses on technology, the new meanings of cultural and alternative futures.

'Gospel for a New Century' comissioned by TRANSFER for 'Pieces of Me'

References

1Marx, Karl. The Communist Manifesto. Verso, 1848.

2Jensen, Robin Margaret. Understanding Early Christian Art. Routledge, 2000.

3Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Random House, 1935.

4Geary, Patrick. “Sacred commodities: the circulation of medieval relics.” The social life of things: Commodities in cultural perspective., Cambridge University Press, 1986.

TRANSFER

TRANSFER  left.gallery

left.gallery

TRANSFER

TRANSFER